The Day Bores Became Exciting

Oilfield down-hole skills may lead to viable large-scale closed-loop geothermal. It's a trend to watch.

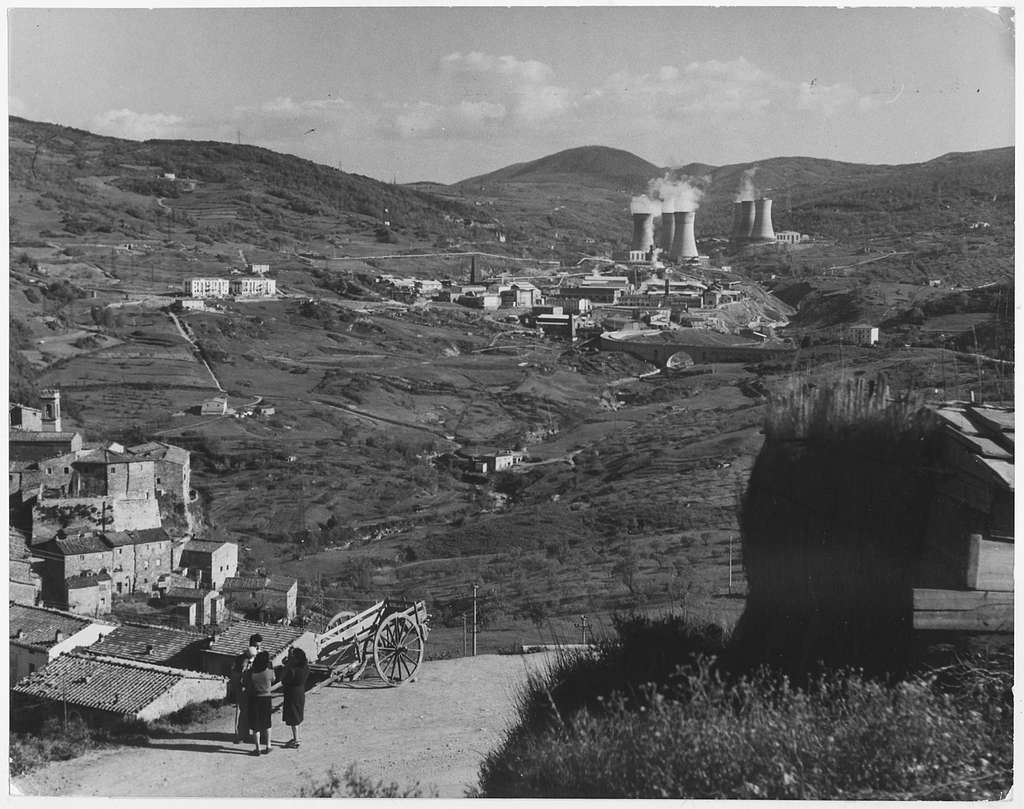

Geothermal is an old form of power, going back to the nineteenth century. Figure 1, in Italy, shows a historical photo of the oldest large geothermal plant operating today.

Almost everybody has heard the story of power and heating in Iceland, where geothermal provides about 20% of the electricity...and plentiful hot water for heating homes.

Seems only fair that a country with "ice" in its name should have endless hot showers.

The trouble with geothermal (well, a trouble; it's not the only one) is its dependence on a constant supply of hot water. Geothermal plants once were built (quite naturally) where steam comes to the surface. In some cases, though—including most of the geothermal plants in Iceland—access to the subterranean reserves of hot water is only gained through deep boreholes that give access to reserves of supercritical water in known underground reservoirs. Sometimes the bore holes are even fracked (hydraulic fracturing) in an attempt to provide artificial pathways for water in hot rock.

For example, the steam supply for the Wairakei Geothermal Power Station in New Zealand has been dwindling for many years.1

Subterranean rock is usually hot, but doesn't always bear water that can be used in geothermal energy. Recently, some companies, including Calgary's Eavor Technologies,2 have solved this problem. They have been applying techniques developed in the oil patch: they drill two deep (up to 7,000 meters) boreholes, linking them with horizontal bores. The vertical boreholes are sealed with cement and metal casings, while the horizontal sections—deep underground, where pipe is difficult to fit—are lined with an alkali-activated sealant. According to Eavor field data and previously-published, peer-reviewed materials research, this alkali-activated sealant is self-healing, stable, and environmentally-safe.3

That's more than hot enough to operate electrical generators (or provide hot showers for vast numbers of chilly sub-arctic urbanites). No water reservoir is needed.

Eavor has a successful demonstration site near Rocky Mountain House, Alberta. It's in the process of building a utility-scale installation at Geretsried, Bavaria, on a site where traditional geothermal drilling has failed to reach viable geothermal reservoirs. Eavor expects to generate first power from the Bavarian plant this year, although construction will continue for another two years.

This is a notable transformation of a technologies and skillsets gained in the Canadian oil patch to a climate-friendly, forward-facing renewable energy project.

Who knew hope could be so boring?

Geothermal energy has been around for a lot of years, and has many different variants and innovative approaches. Please don't mistake this short, simplified summary for a complete examination of what's going on in this old but expanding field. Want to learn more? For such a relatively small nation, New Zealand has a lot of geothermal installations and tons of geothermal potential. Their summary of geothermal—side by side with a rich catalog of examples—is a good place to start reading more deeply.4

Reading

- Grant, Malcolm. "Reservoir Engineering of Wairakei Geothermal Field." In Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, 197–212. Dordrecht: Springer, 1988

- Eavor. “Technology - Eavor - Closed-Loop Geothermal, Unlike Any Other.” Accessed May 23, 2025. https://eavor.com/technology/.

- Zhang, Lei. "Crack Self-Healing in Alkali-Activated Materials: From Mechanisms to Strategies for Enhancing the Healing Efficiency." PhD diss., The University of Western Ontario, 2021. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/context/etd/article/10808/viewcontent/PhD_Thesis_Lei.pdf.

- “Geothermal Energy Generation | Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment.” Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/building-and-energy/energy-and-natural-resources/energy-generation-and-markets/geothermal-energy-generation.