Cook Islands: A Cautionary Tale

Canaries and coal mines and coconuts!

A little over ten years ago, a group of friends with a shared interest in technology and energy started thinking about ways to reduce consumption and make clean energy more accessible. This little group was the first generation of Sweetlightning.

At the time, awareness of climate change was growing with Al Gore’s film “An Inconvenient Truth”1 having won awards and contributed to his Nobel Peace prize. Governments around the world were focusing attention and resources on the climate with the 2015 Paris Climate Accords about to happen.

It turned out two members of Sweetlightning had already done some work together in the Cook Islands. Working for the National Energy Committee (NEC), they were part of a small team who developed a Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP)2. One of the team, James, operated businesses on Rarotonga and was very familiar with the energy issues facing the islands. The SEAP was a well-thought-out strategy to transition the Cook Islands from the electricity grid, then powered 100% by diesel generation, to renewable power, primarily PV (photovoltaic or solar) power. The plan was enthusiastically supported by the government of the time.

The Cook Islands is a small island state comprised of fifteen islands spread over nearly 2 million kilometres of the Pacific Ocean. It is located between the latitudes 8 degrees and 23 degrees south and longitudes 156 degrees and 167 degrees west (about 2800 km NE of New Zealand). The fifteen islands are divided geographically into a Northern and Southern group. "Low coral atolls" describes the Northern group of islands (Suwarrow, Nassau, Pukapuka, Rakahanga, Manihiki and Penrhyn. In the Southern group, only Rarotonga is a volcanic island. The remaining southern group (Aitutaki, Manuae, Takutea, Atiu, Mitiaro, Palmerston, Mauke, and Mangaia) are a mix of raised coral atoll or makatea, atoll and sand cay. 3

For this article we interviewed James, who still lives and works in the Cook Islands, and asked him to reflect on the original plans for its renewable energy transition, comment on what has transpired since, and bring us up to date the current status of renewables.

(The transcript has been edited for clarity and length.)

Q: James, can you describe the power generation situation in the Cook Islands prior to your work on the renewable energy project?

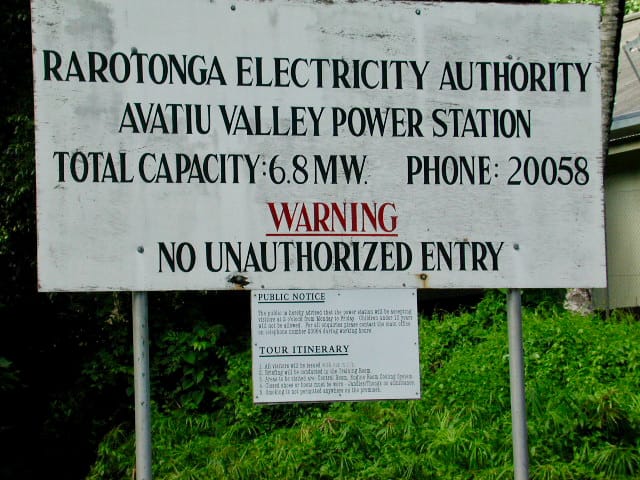

James: The Cook Islands were 100% dependent on fossil fuel. Rarotonga's generation was from a power station based in the back of town, and that power station was run purely on diesel oil (or diesel fuel) imported predominantly from New Zealand, Singapore, or Fiji. We started to talk about ways in which we could try to mitigate those potential disasters that the Cook Islands invariably ends up facing, primarily with late shipments, power blackouts, and power brown outs. So we embarked on trying to find ways and solutions to get the Cook Islands into a more diversified form of energy.

Q: So back then the Cook Islands were 100% powered by diesel, imported diesel fuel. Rarotonga's power ran through a big diesel generator for the whole island, with all the problems that entailed.

James: And not just Rarotonga, we're talking 15 islands, 12 or 13 of them are inhabited, spread over almost 2 million square kilometers of ocean, and every one of those islands is reliant on on generators using diesel fuel.

Q: Tell us a little about how the energy situation affected you as a business owner.

James: I had three grocery stores both retail and wholesale to small community stores. And the grocery stores imported 99% of its of its product from overseas, whether it was from Canada, America, Australia and predominantly New Zealand. And so we had a lot of frozen goods and a lot of chilled products, frozen lamb and frozen beef, potatoes, carrots, all of that was chilled. So they came in refrigerated containers, and then we would put those into our large cold stores. So that would definitely be the reason why we've got high energy costs. But in saying that, even the small corner stores, little convenience stores with one or two chillers and one or two freezers, their electricity costs would probably run about the same kind of cost metric as it was for mine. For example, I would look at a couple of my wholesale customers back then and their businesses were much, much smaller by comparison. And with only one drinks chiller and one or two freezers, they were looking at a cost of about $4000 to $5,000 per month in electricity bills. That's New Zealand dollars. And that's a huge amount of money for a business that's probably making about $300 to $400 a day, which you know, has to take care of the cost of the goods and wages. So most people that are business owners here, because of the high cost of doing business, end up working for free.

Q: Tell us how the National Energy Committee and the Sustainable Energy Action Plan got going?

James: I was involved in various boards, including the National Energy Committee. We had a team of about five or six of us. The minister of energy at the time was my good friend, Tangata Vavia. He was one of those guys that really wanted to see some kind of change. I think the biggest job that we had to do was not just to identify the type of technology that was going to be used, but more so to develop policies, to be able to help the government make its decisions. The result was the SEAP. So I had either role as a committee member, chaired it for a while as well, for the National Energy Committee.

As often happens, soon after the (SEAP) report was done and before implementation and fund raising could begin, there was a change in government.

This was the fate of the SEAP.

Still funding for renewable energy projects was being made available by the developed nations based on the 2015 and subsequent climate accords. The Cook Islands was able to get funding to convert power generation to solar.

In 2015 the Asian Development Bank, the EU, and New Zealand provided what eventually amounted to roughly NZ $30 million dollars to convert power generation from diesel to solar.4 The installation projects were well managed and staged by Entura, a speciality consulting firm. The outlying islands, both Northern and Southern, had PV installations that were initially successful. However, within a few years some of the islands began experiencing outages and failures of the new power grids, and required additional funding and outside expertise to get these failures resolved. Progress essentially stopped when the outlying islands were done, and today Rarotonga, the largest and most populated island, is still powered (roughly 90%, depending on which metrics you choose) by diesel generation.

What happened?

Political infighting and short-term thinking prevented the thoughtful structuring of setting rates and ensuring that fair electricity costs were collected and available to replace worn equipment, put in monitoring systems and train local staff to manage the installations. The islands in the Northern group are lightly populated, and an estimate at the time was that the cost of the installation on some islands was up to $64,000 per household. No billing was implemented, so the power ended up being free. The constituents of some government leaders were from these islands so there was considerable concern that this was done for political reasons.

On the island of Pukapuka the entire system failed due to battery degradation. The system was repaired following a battery replacement project funded buy the NZ government. A 170kVA diesel generator was installed to provide backup for the solar panels.

Again, the objective here is not to pick on the Cook Islands. There are more than enough similar stories from other Pacific islands (Tuvalu, Marshall Islands, etc) to make the case that these are not isolated incidents. As with the Cook Islands experience, many of these initial failures have been resolved and lessons learned.5

It didn’t have to be that way.

Had the original SEAP recommendations been implemented, even some of them, the outcome could’ve been far different. The report included plans for net metering, fair billing to customers, allocating money for maintenance and operations, and even consideration for promoting Electric vehicles amongst other plans. The aspiration of the plan was to solve these problems as part of implementing renewable energy and in so doing become a model for how this could be done in other nations.

The introduction to the SEAP report invoked the story of canaries in the coal mine, making the case that the Cook Islands could be the canary for the rest of the world facing climate change. The Cook Islands have a distance to go in achieving its renewable energy goals. It seems they would benefit by re-reading the original plans to help restart their path forward.

And the canary for the rest of us….

Reading

- Guggenheim, Davis, dir. An Inconvenient Truth. 2006; Los Angeles: Paramount Classics, 2006. Film.

- “Cook Islands Sustainable Energy Action Plan | PCREEE.” Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.pcreee.org/publication/cook-islands-sustainable-energy-action-plan?page=4.

- Green Climate Fund. Cook Islands Country Programme. March 14, 2019. Green Climate Fund.

- New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. “Cook Islands Renewable Energy Sector Project,” 2015.

- Liebenthal, Andres, Subodh Mathur, and Herbert Wade. Solar Energy: Lessons from the Pacific Island Experience. World Bank Technical Papers. The World Bank, 1994. https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-2802-6.