Misinformation, Disinformation, Malinformation, and Distrust of Climate Science

Misinformation, disinformation and malinformation are forms of rampant pollution of the information ecosystem. This pollution is toxic, promoting distrust in science, and holding back efforts to combat climate change.

Carl Sagan, in his 1995 book, The Demon-Haunted World, wrote

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what is true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness.”1

Sagan’s foreboding was an eerily prescient prediction of the world now, if you substitute the internet and social media for crystals and horoscopes, and if you include most of the world’s democracies, not just the USA.

In ancient Rome, during the struggle for succession that followed the assassination of Julius Cesar, his nephew Octavian embarked on a smear campaign of his political rival, Marc Antony. Via songs, poetry, and phrases on coinage, he painted Antony as a degenerate who couldn’t be trusted, because of his love affair with the foreigner, Queen Cleopatra of Egypt – his loyalty to Rome was therefore suspect and his judgement was questionable. It largely worked. Octavian became Cesar Augustus, and continued to vilify Antony’s character even after Anthony's defeat and death.2 Sound familiar?

The topic covers a vast amount of ground and an article like this one can’t discuss it all. We’ll delve into the reasons that misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation are so much more widespread in our modern world, but first we’ll focus what they are, on the distrust of climate science that they have engendered, and the harms they cause.

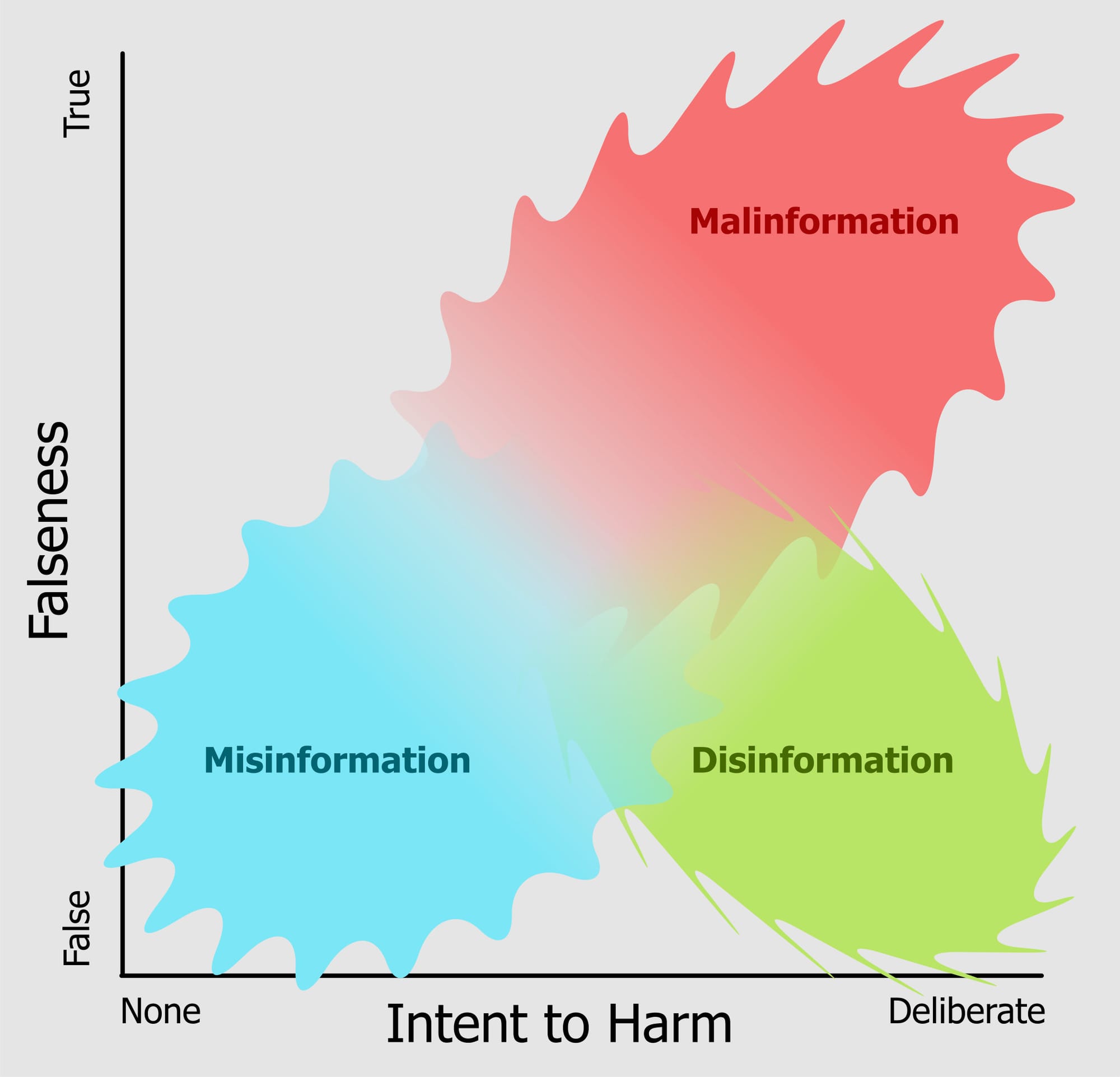

Princeton University has posted a guide with succinct definitions of these skewed forms of information, which are worth quoting verbatim:3

Misinformation is defined as false, incomplete, inaccurate/misleading information or content which is generally shared by people who do not realize that it is false or misleading. This term is often used as a catch-all for all types of false or inaccurate information, regardless of whether referring to or sharing it was intentionally misleading.

Disinformation is false or inaccurate information that is intentionally spread to mislead and manipulate people, often to make money, cause trouble or gain influence.

Malinformation refers to information that is based on truth (though it may be exaggerated or presented out of context) but is shared with the intent to attack an idea, individual, organization, group, country or other entity.

A 2017 report done for the Council of Europe characterizes all of these as parts of “Information Disorder”4, and visualizes them along the dimensions of falseness and harm.

Here is one example. In 2023, elected Councillors in Oxfordshire, UK, proposed a traffic congestion management scheme, essentially a local version of a process successfully used in Belgium and elsewhere. The scheme was immediately accused of being a “climate lockdown” conspiracy that would see residents locked in their neighbourhoods, unable to move about.5 Most of the misinformation actors that promoted the conspiracy theory were not from the area affected. Residents of Oxford were confused and concerned. The Councillors suffered widespread harassment and abuse. The result was that a sensible, proved approach faced opposition and delay, to say nothing of the stress and chilling effect on the elected local government officials.

A 2021 study6 that looked at 180 of ExxonMobil’s internal company documents, and external communications (e.g. peer-reviewed publications, advertorials in the New York Times), dating from 1977 onward, found that while their peer-reviewed material acknowledged anthropogenic climate change, their public anthropogenic global warming messaging strategy was virtually the same as that previously used by the tobacco industry . The public messaging downplayed the reality and seriousness of climate change by characterizing it as climate risk. They attempted to shift responsibility to individuals by framing global warming as a challenge of meeting individuals’ energy demands with fossil fuels. The study says that the company has “used rhetoric of climate “risk” and consumer energy “demand” to construct a “Fossil Fuel Savior” (FFS) frame that downplays the reality and seriousness of climate change, normalizes fossil fuel lock-in, and individualizes responsibility.” These tactics have contributed to doubt in the minds of the public and politicians, and have very likely impeded or slowed public policy solutions to climate change.

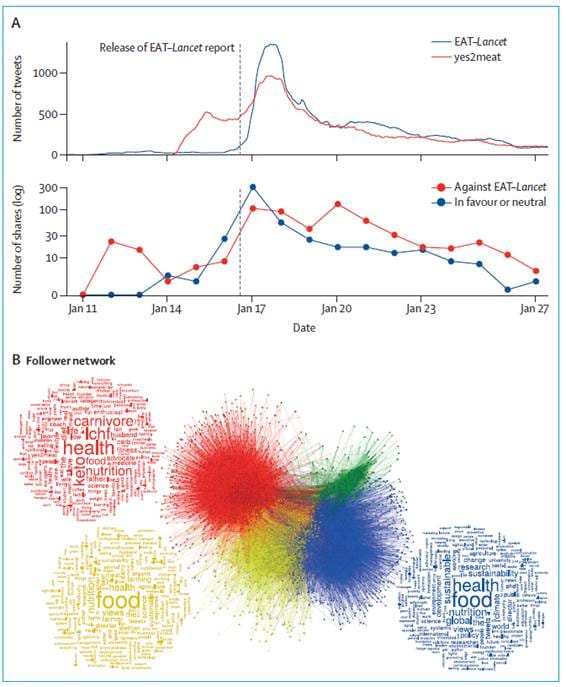

Another relatively recent example was the online reaction to a 2019 study published in The Lancet. The study7 was an attempt to answer the question of whether and how the world can feed a future population of 10 billion people on a healthy diet within planetary boundaries (as measured by climate change, land-system change, freshwater use, nitrogen cycling, phosphorus cycling, and biodiversity loss). The study concluded that it was possible, if we shifted to more plant-based diets and ate less meat. Online backlash was immediate and fierce, featuring misinformation, conspiracy theories, and personal attacks on the report’s authors. Many posts and articles featured the hashtag #yes2meat. A follow-up study8 that analyzed this backlash, via the number of tweets for and against, confirmed that the digital counter movement organized rapidly, “essentially dominating online discussions about the EAT–Lancet report in intriguing and worrying ways.” Counter movement tweets and articles about the report were about ten times more likely to be negative than positive or neutral.

A subsequent investigation9 by a leading newspaper found that the campaign was likely coordinated by a PR firm on behalf of the Animal Agriculture Alliance.

It is not uncommon to see claims that the science is not settled on whether climate change is happening or whether it is caused by human activity. The malinformation claims are usually based on science papers that question climate change in some way or another. While a few scientists are skeptics, they are in a tiny minority. The overwhelming scientific consensus in the peer-reviewed literature, greater than 99% as of 2021, is that contemporary climate change is human-caused.10

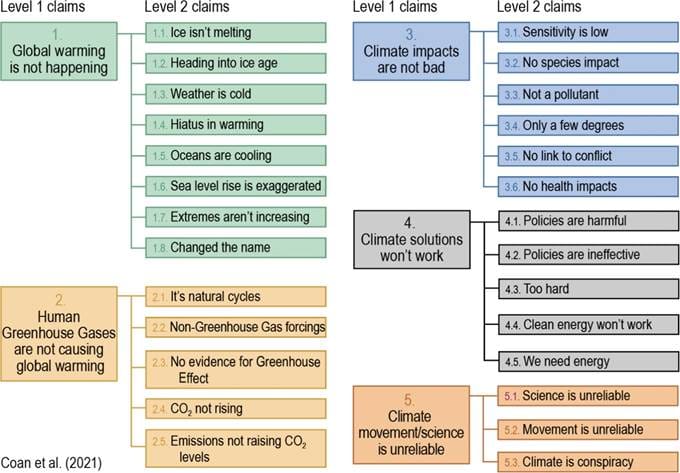

The example above is just one of the many malinformation counter-claims about climate change. Some researchers have developed a whole taxonomy of contrarian climate claims11:

Why is information disorder so prevalent and why do distortions, myths, untruths and conspiracies spread so much faster, and seemingly more widely, than the facts?

Part of the difficulty is that none of us, as individuals, do a perfect job of detecting bullshit, and further, there is a gap between how good we think we are and how good we actually are. There are differences between broad groupings, though, with those with higher education doing better, baby boomers doing better than Gen-Z, and more liberal doing better than extremely conservative.12 There isn’t much of a gender gap.

Another major reason is where many people now get their news: social media. The very nature of social media is a problem. Chen13 argues that social media has inherent features that promote the spread of misinformation. Social media promotes user-generated content (which may not be accurate), supports dynamic network structures (therefore rapidly changing), has complex recommendation algorithms which prioritize emotional response (which is characteristic of much misinformation), and promotes bubbles (which become echo chambers that preclude new/factual information from getting in). Accuracy is not a prime consideration in how social networks propagate information.

What can be done to combat information disorder?

The 2017 Council of Europe report made 34 recommendations, grouped by actions that could be taken by technology companies(13), national governments(6), media organizations(8), civil society(2), education ministries(3), and funding bodies(3). The recommendations are diverse, ranging from changes in the way that technology companies operate, to policy changes, to regulation, collaboration, and education.

What kind of education?

Debunking false information, after the fact, is insufficient, as, once people are exposed to false information, it is difficult to correct. More effective is “pre-bunking”, a process akin to medical inoculation, to pre-emptively build psychological resistance to malicious manipulation attempts. Researchers designed an on-line game, “Bad News”14 in which players were tasked with creating “fake news”, thereby learning, in the process, about half a dozen common disinformation techniques. Players’ ability to recognize misinformation improved significantly after playing the game. Intriguingly, the inoculation effect did not vary significantly with age, gender, education level, or political ideology.

The problem of misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation, is broad, complex, and deep. Some liken the problem to pollution of the “information ecosystem”.15 Like natural ecosystems, everything is connected to everything else, so that any individual action may have unintended negative consequences. In the information ecosystem, for example, a fact-checking or debunking effort might actually make more people aware of the original false information than if the debunking had not occurred. A broader, more coordinated and considered approach is needed.

In this article we have just skimmed the surface of the issue. Just as with natural ecosystems, our understanding will no doubt continue to increase, and we can hope that more interconnected, holistic solutions will emerge and be implemented.

Reading

- Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. 1st ed. New York, USA: Random House, 1996. Chapter 2, P 26

- Verishagen, Nina, and Diane Zerr. “1.4 The History of Disinformation,” March 1, 2023. https://www.saskoer.ca/disinformation/chapter/1-4-the-history-of-disinformation/.

- Princeton Public Library. “Misinformation, Disinformation & Malinformation: A Guide.” Accessed May 23, 2025. https://princetonlibrary.org/guides/misinformation-disinformation-malinformation-a-guide/.

- Freedom of Expression. “Information Disorder - Freedom of Expression - Www.Coe.Int.” Accessed May 23, 2025. https://www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression/information-disorder.

- “Oxfordshire Climate Lockdown: How a Traffic Scheme Became a Conspiracy | Logically Facts.” Accessed June 26, 2025. https://www.logicallyfacts.com/en/article/oxfordshire-climate-lockdown-how-a-traffic-scheme-became-a-conspiracy.

- Supran, Geoffrey, and Naomi Oreskes. “Rhetoric and Frame Analysis of ExxonMobil’s Climate Change Communications.” One Earth 4, no. 5 (May 21, 2021): 696–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.04.014.

- Willett, Walter, Johan Rockström, Brent Loken, Marco Springmann, Tim Lang, Sonja Vermeulen, Tara Garnett, et al. “Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems.” The Lancet 393, no. 10170 (February 2, 2019): 447–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4.

- Garcia, David, Victor Galaz, and Stefan Daume. “EATLancet vs Yes2meat: The Digital Backlash to the Planetary Health Diet.” The Lancet 394, no. 10215 (December 14, 2019): 2153–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32526-7.

- Carlile, Clare. “Revealed: Meat Industry Behind Attacks on Flagship Climate-Friendly Diet Report.” DeSmog (blog), April 11, 2025. https://www.desmog.com/2025/04/10/meat-industry-red-flag-animal-agriculture-alliance-behind-attacks-flagship-climate-friendly-diet-report-eat-lancet/.

- Lynas, Mark, Benjamin Z Houlton, and Simon Perry. “Greater than 99% Consensus on Human Caused Climate Change in the Peer-Reviewed Scientific Literature.” Environmental Research Letters 16, no. 11 (October 2021): 114005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966.

- Coan, T. G., Boussalis, C., Cook, J. & Nanko, M. O. Computer-assisted classification of contrarian claims about climate change. Sci. Rep. 11, 22320 (2021).

- Kyrychenko, Yara, Hyunjin J. Koo, Rakoen Maertens, Jon Roozenbeek, Sander van der Linden, and Friedrich M. Götz. “Profiling Misinformation Susceptibility.” Personality and Individual Differences 241 (July 1, 2025): 113177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2025.113177.

- Chen, Panpan. “The Spread Mechanism of Misinformation on Social Media.” Journal of Computer Technology and Electronic Research 1, no. 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.70767/jcter.v1i3.407.

- Roozenbeek, Jon, Sander van der Linden, and Thomas Nygren. “Prebunking Interventions Based on ‘Inoculation’ Theory Can Reduce Susceptibility to Misinformation across Cultures.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1, no. 2 (February 3, 2020). https://doi.org/10.37016//mr-2020-008.

- Deutsche Welle. “Detoxing Information Ecosys t ems,” April 18, 2024. https://akademie.dw.com/en/detoxing-information-ecosystems-a-proactive-strategy-for-tackling-disinformation/a-68820226.